In the run up to Halloween, and a highly anticipated trip to London the day after, I decided to do some proper posts on the murders in Whitechapel in 1888 by the notorious Jack the Ripper. It’s a subject that has long fascinated me, and in some of my previous posts on this blog I briefly outlined some of the murders as we had just returned from London where we had followed the Rippers trail with the help of the fantastic Haunted London app. It was so atmospheric and fascinating I decided that I would like to discover more and potentially become a Ripperologist. I can’t wait for our trip on the 1st as we have booked a hotel in the heart of Spitalfields on the edge of Whitechapel where Jack roamed and I am excited to get some creepy night time pictures in some of the unchanged areas and alleyways surrounding the hotel.

So lets begin by taking a step back in time to the dank, dark, and dangerous streets and thoroughfares of the East End of London in the late 1880’s. With my trusty Jack the Ripper Casebook by Richard Jones as my guide, I will try to set the scene for these grizzly crimes.

It is the year after Queen Victorias Golden Jubilee, 1888. London is expanding, having just experienced a period of sustained economic growth, and a new middle class has been created due to the need for managers, clerks and administrators. However, things are starting to change with growing competition coming from Germany and America challenging our Industrial dominance. A slump in trade has caused mass unemployment, and thousands of people are on the brink of poverty. There is unrest among the lower classes, and socialism is becoming more and more popular. In 1886 and 1887 there are several riots and protests on the streets of the West End, with several shops being looted and property damaged. The middle and upper classes fear a revolution is inevitable, and focus their nervousness on Whitechapel and the East End.

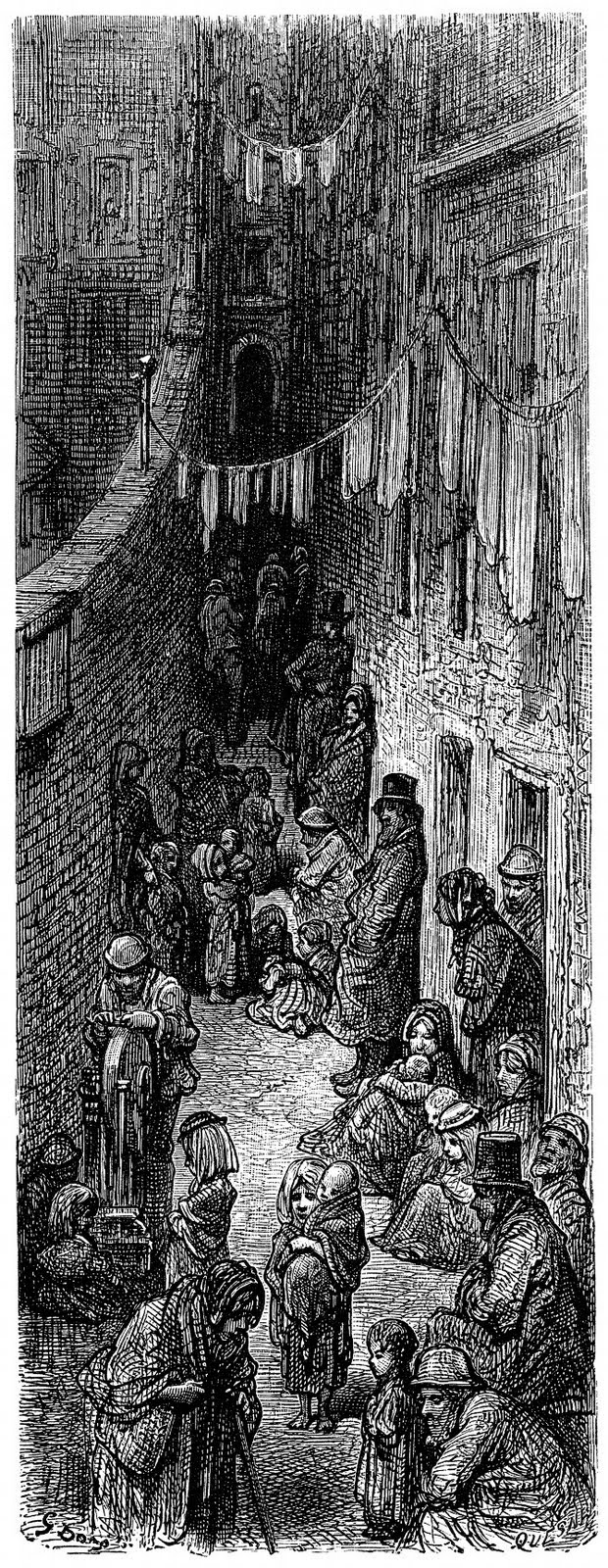

Whitechapel had some of London’s worst slums, highest death rates and the most dreadful living conditions. Every day was a constant fight for survival, where people were endlessly fighting for jobs in order to feed their families. The area was densely populated, with the worst area seen to be the “evil quarter mile” which consists of a series of thoroughfares such as Thrawl Street, Flower and Dean Street, and Wentworth Street. The dregs of society were crammed into rank dwellings with sometimes as many as 20 people sharing a house. In some cases, entire families were forced to live in one room, and in dire situations they would sublet a corner to a lodger.

The “evil quarter mile” was the largest provider of accommodation, with many common lodging houses in which thousands of men, women and children were crammed into dormitories. Many of these lodging houses were above board and orderly, however a large number were dens of iniquity inhabited by dangerous criminals, prostitutes and mentally unstable characters. The upper and middle classes virtually never ventured into these slums, but if the wind was blowing in the wrong direction they were reminded of their existence due to a foul stench of sewage or the areas slaughterhouses and factories.

A quarter of a million people lived in Whitechapel, 15,000 of it’s residents were classed as homeless. Disease, hunger, neglect and violence claimed the lives of one in four children before they reached the age of five. A wealthy shipping magnate turned philanthropist and social reporter, Charles Booth, claimed that as many as 60,000 East End men, women and children loved their daily lives on the brink of starvation.

At this time, a surge of immigrants flooded into the area, mostly consisting of jews. Throughout the 1880’s the Jewish population had surged from 45,000 to 50,000. The mass unemployment due to the economic depression saw the Jews vilified for stealing English jobs. Many Jewish workers were willing to work long hours for minimal wages, and so were accused of underhand methods in order to obtain jobs over the English populace. In June of 1887, a Jewish man named Isreal Lipski who was lodging at a house in Batty Street, forcibly poisoned another Jew and fellow lodger named Miriam Angel by pouring nitric acid down her throat. He was hanged for the murder, but it did increase the anti-Semitic feeling in the area. “Lipski” was by 1888 being used as a term of abuse towards jews from Gentiles.

The harsh and demoralising living conditions that many were forced to endure in the East End were blamed for many young women turning to the streets in order to make a living. They were labelled “unfortunates”, and were forced to become prostitutes in order to provide for themselves and their families. A prostitute could make more in one night than many could in one week in a factory or sweat shop, and this money would go towards food and lodging, but more importantly, towards the drink that would allow them to forget their horrific existence. Many of these unfortunates could conduct their business relatively safely in brothels. That was until the well-meaning campaign of a local brewing dynasty heir, Frederick Charrington, caused the closure of 200 of the areas brothels, thus forcing the displaced prostitutes out onto the streets and into the path of the Ripper.

In my next post, I will talk about the policing of the case and the inspectors and officers assigned to bring the murderer to justice.